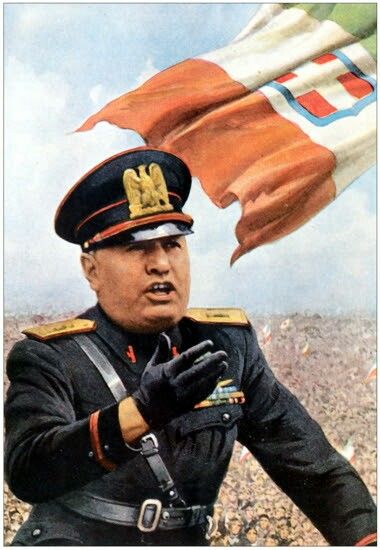

Hitler considered “Il Duce” – Benito Mussolini – one of his role models (actually, the most influential one). His highly successful “March on Rome” became an inspiration for the (pathetic) Beer Hall Putsch. And Hitler’s economic policies and reforms followed the “blueprint” derived from also highly successful economic policies of “Il Duce”.

Hitler considered “Il Duce” – Benito Mussolini – one of his role models (actually, the most influential one). His highly successful “March on Rome” became an inspiration for the (pathetic) Beer Hall Putsch. And Hitler’s economic policies and reforms followed the “blueprint” derived from also highly successful economic policies of “Il Duce”.

Italy and Germany shared a common economic problem – insufficient strategic resources. To rectify this problem, Mussolini’ embarked on intensive development of all available domestic sources (Hitler would add to that development of whole industries that would produce substitute products).

And pursued aggressive commercial foreign policies – securing bilateral raw material trade agreements (essentially barter-style), and strategic colonization (Lebensraum Italian-style).

Although a disciple of the French Marxist Georges Sorel and the main leader of the Italian Socialist Party in his early years, Mussolini abandoned the theory of class struggle for class collaboration.

To facilitate transition from the former to the latter, Il Duce’s government intervened directly (on as needed basis) to create a collaboration between the industrialists, the workers and the state (making the two former essentially the servants of the latter).

Collaboration based on the fundamental principle of corporatism. Which called for the structuring of the whole society as a system of corporate groups – agricultural, labor, military, scientific, or guild associations – on the basis of their common interests.

Which will (in theory) create a powerful synergy between these groups – with each group performs its designated function flawlessly, society will function harmoniously – like a human body (corpus) from which its name derives.

Adolf Hitler structured his Führerstaat in much the same way, only replaced corporatism with national-socialism (which is actually not that much different from the former).

Mussolini ultimately banned all trade union except the fascist ones – and Hitler did the same, replacing all German trade unions with just one – German Labor Front (DAF). Il Duce made both strikes and lock-outs illegal – and so did Hitler.

Mussolini declared autarky (self-sufficiency in all key economic resources) as his long-term strategic objective – and so did Hitler a decade later. Mussolini embarked on an ambitious public spending program financed by runaway budget a deficit – and Hitler would pursue practically identical economic and financial policies.

Mussolini spent Italy into a structural deficit that grew exponentially – and so did Hitler. In Mussolini’s first year as Prime Minister in 1922, Italy’s national debt stood at 93 billion lire. By 1934, it rose to 148,646,000,000 lire (i.e. increased by half). Hitler’s numbers were even more astounding – in 1939 its national debt reached 150% of Gross Domestic Product of Germany.

Mussolini’s spending on the public sector, schools and infrastructure was lavish (to put it mildly). He instituted a program of public works hitherto unrivaled in modern Europe. The program that was eclipsed only by the Nazi one.

Mussolini’s administration devoted 400 million lire from the state budget for school construction between 1922 and 1942, compared to only 60 million lire between 1862 and 1922. Which was not a surprise at all as Mussolini “in his previous life” was a schoolteacher.

Bridges, canals and roads were built, hospitals and schools, railway stations and orphanages were erected; swamps were drained and land reclaimed, forests were planted and universities were endowed.

As for the scope and spending on social welfare programs, Italian fascism compared favorably with the more advanced European nations and in some respect was more progressive (although not nearly as progressive as its Nazi counterpart). When New York city politician Grover Aloysius Whalen asked Mussolini about the meaning behind Italian fascism in 1939, the reply was: “It is like your New Deal! [only much better]”.

By 1925, the Italian government had embarked upon an elaborate welfare program that included food supplementary assistance, infant care, maternity assistance, general healthcare, wage supplements, paid vacations, unemployment benefits, illness insurance, occupational disease insurance, general family assistance, public housing and old age and disability insurance.

A decade later Adolf Hitler would follow this blueprint almost to a ‘T’.

To finance these programs, Italy’s first Fascist government implemented a large-scale privatization policy between 1922 and 1925. And so did Adolf Hitler – ten years later.

The conclusion is obvious: Adolf Hitler pretty much followed in the footsteps of another dictator – Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini. Which was a smart decision – why “reinvent the wheel” if one can copy (adapting when necessary) proven solutions that work? Hitler did exactly that – and in many way became much, much more successful than his role model.

Hence it is not a surprise at all that Hitler was an admirer of Mussolini almost from the get-go (interestingly enough, Churchill was, too). Il Duce, however, did not even like Hitler at first. Even years later, Mussolini openly expressed his frustrations with Hitler’s actions and policies (before the latter proved to be very successful, of course).

Their first meeting together in 1934 was particularly icy. Mussolini listened to Hitler talk at length without saying much (this would become characteristic of just about their meetings) and afterwards wrote Hitler off as essentially insane.

He believed Hitler’s ideas of race and the existence of superior races were batty, and dismissed them out of hand. After their first meeting, Mussolini remarked dismissively, “He’s just a garrulous monk.”

However, the invasion of Ethiopia undertaken by Mussolini in 1935 (and unconditionally supported by Adolf Hitler) and especially the Spanish Civil war where German and Italian volunteers fought on the Nationalist side brought them closer together.

And when Wehrmacht had to come to the aid of the Italian Army in Yugoslavia, Greece and especially in North Africa, Mussolini became almost completely dependent on Hitler. And thus had no other choice but to radically warm up to the latter.

Whatever faults the two may have taken with each other (and there were some), the rescue of Mussolini from the hotel he was imprisoned at in 1943 showed that Hitler genuinely considered Mussolini a friend. And the feeling was mutual; when the German commandos freed him, Mussolini commented, “I knew my friend Adolf Hitler would not desert me.”

After Mussolini was rescued by the Germans, the relationship became a lot more one-sided. The Germans occupied the northern and central sections of Italy (with the Allies controlling the south and Sicily) and Mussolini was installed as the head of the so-called “Italian Social Republic”.

However, he was little more than a German puppet and he knew it. So by this point, it was Hitler and the SS who were calling the shots on any substantial matter of policy in the parts of Italy that were still controlled by the Fascists. It was a fulfillment of Mussolini’s worst fear in the truest sense: becoming a mere lackey of the Germans.

Contrary to a popular misconception, Benito Mussolini was not a role model for Adolf Hitler. Not even an inspiration (let alone a teacher). They were simply way too different – and so were Italy and Germany.

Contrary to a popular misconception, Benito Mussolini was not a role model for Adolf Hitler. Not even an inspiration (let alone a teacher). They were simply way too different – and so were Italy and Germany.